Maker and Muse Exhibit

I recently visited the exhibit Maker and Muse, Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago. Curated by Elyse Zorn Karlin, author of Jewelry and Metalwork in the Arts and Crafts Tradition, the exhibit explores the multiple roles women played in the creation of early 20th century art jewelry as makers, patrons, and subjects. About half of the 250 pieces in the exhibit are drawn from the collection of Richard H. Driehaus – founder of the museum – and half are on loan from other museums and private collections. I was in Chicago to attend the annual conference of the Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts (ASJRA) which was focused this year on the subjects covered in the museum exhibition. For my post on the conference click here.

The Museum, housed in a well-preserved gilded age mansion full of period decorative art, provided a lush backdrop for the jewelry and gives a sense of the context in which the grandest pieces might have appeared when new.

Art Jewelry is a term that encompasses several design movements that took place from the late 19th century to the onslaught of WWI: Arts and Crafts in Great Britain and the United States, Art Nouveau in France, and Jugendstil or Secessionist in Germany and Austria. The pieces in the exhibit range from the modestly-priced silver pieces produced by Chicago’s Kalo Shop to exceptional pieces produced by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Rene Lalique. However, what the jewelry produced by these movements has in common is that it “deviated from mainstream jewelry of its time and was created as alternative ornamentation for those with artistic and individualistic taste” according to Karlin.

Encompassing the entire second floor of the museum, the exhibit is organized into five thematic rooms: With a Hammer in Her Hand, Women and the British Arts and Crafts Movement; American Art Jewelry, Louis Comfort Tiffany; Jewelry as Art, Germany and Austria in the Early 20th Century; Metamorphosis, The Female Figure in Art Nouveau; and Beautiful, Useful, and Enduring, Chicago Arts and Crafts Jewelry. There are many spectacular pieces of jewelry in the exhibit and it’s important to note that I couldn’t get good photos of some of these pieces because of reflections from overhead lighting; so, if you make it to the exhibit, there are lots of surprises!

The first room contains the work of Arts and Crafts jewelers in Great Britain, many of whom were women. According to Karlin, “The coincidence of many factors – the suffragist movement, dress reform, new thoughts about design, the influence of the Pre-Raphaelite painters and the designer William Morris, and new roles for women in society – helped bring about” the new role for women as maker. The Arts and Crafts movement in Great Britain was a reaction to the industrial revolution and the poor quality of design – and the poor quality of life of factory workers – that resulted from it. In doing so it looked back towards an idealized period of handcrafted work produced by medieval craft guilds. In England and the United States much of this work was geared to the emerging middle class and made of silver and colored stones although, as seen below, the work of Tiffany and a few other jewelers utilized gold, diamonds, and precious colored stones.

The second room is devoted to the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, with a small foray into the work of Marcus and Co., Tiffany’s main competitor. While Tiffany’s work is famous, what is less well-known is that the heads of his jewelry workshop were women. Julia Munson was the first head of this workshop, which was separate from the mainstream fine jewelry being produced by Tiffany and Company. Munson began this job in 1902, the same year Tiffany opened this workshop, and continued until her marriage in 1914; while Tiffany was somewhat progressive in hiring a woman to lead his jewelry workshop, he nevertheless had a policy that married women should not work. Munson was replaced by another woman, Meta Overbeck, who remained in this position until the workshop was closed in 1933. Though always intended for a moneyed audience, and made of gold, diamonds and precious stones, Tiffany and Marcus often used less-precious stones like opals as the centerpiece of their designs.

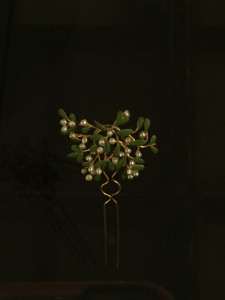

Architect-designers with an interest in Gesamtkunstwerk – the German word for the unity of all arts forms in the built environment – were behind the jewelry of the German and Austrian design movements known as Jugendstil and Secessionist. Women played less of a role as makers in these movements than they did in the Arts and Crafts movements of England and the United States, although the female reform clothing designer Emilie Floge was an active participant and Gustav Klimt’s muse. Many of the pieces in the exhibit were by Josef Hoffmann and Kolomon Moser of the Weiner Werkstatte (Vienna Workshops). While often constructed of silver and colored stones Wiener Werkstatte pieces were not inexepensive; one of the goals of the Werkstatte was to pay their workers a decent wage, which had the effect of raising prices.

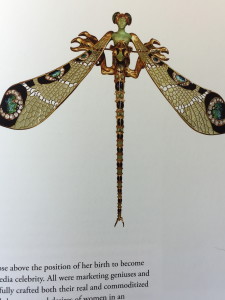

While rarely involved in the making of Art Nouveau jewelry (with the exception of Elizabeth Bonte who made sublime jewelry out of horn), women were often its subject. The sensual curves, symbolism, and imagery of the jewelry often took the form of women. In contrast to the diamonds and platinum prevalent in mainstream fine jewelry of the time, Art Nouveau jewelry embraced colored stones, gold, enamel, and non-precious materials like horn.

Women were often depicted in highly sexualized ways, particularly in French Art Nouveau jewelry. Even lush images of nature, while beautiful at first glance, contained symbols of sex, death, decay, and danger. Many of the women who wore this jewelry were on the fringes of society like actresses and courtesans.

Chicago was a major center of Arts and Crafts jewelry in United States. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago was a training ground for women designers; in addition, several prominent society women were both practitioners and proponents of Arts and Crafts jewelry and design.

Founded by six women graduates of the Art Institute the Kalo Shop became a successful venture and a Chicago fixture that lasted until 1970 when the last of its silversmiths died off. Most of the production of Chicago Arts and Crafts jewelers was moderately priced and aimed at the middle class or upper class with progressive values. Many of the society women were also active in the suffrage movement and settlement house movement.

The curator of the exhibit, Elyse Zorn Karlin, is one of the founders and co-directors of the Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts (ASJRA). In conjunction with the exhibit the ASJRA held its annual conference in Chicago this year. I’ll be writing a blog post about the conference shortly.

The Book

In conjunction with the exhibit an excellent book has been published. Also titled Maker and Muse, Women in Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry, the book has been edited by Elyse Zorn Karlin and has chapters on each of the themes of the exhibit written by experts in their fields. This book is a valuable addition to a library of books about jewelry and art.

Also in Chicago…

The Art Institute of Chicago is one of the world’s great museums and should be on every visitor’s agenda. Well known for its superb collection of Impressionist paintings, what is less well-known is that it has an excellent collection of jewelry. Its collection of Renaissance jewelry is hidden away in a back corner of the second floor behind arms and armor, but worth seeking out.

In addition to being fairly sizeable (for something so rare), the Renaissance jewelry is displayed in a way that is particularly useful for jewelry lovers: most of the pieces are hung so that you can see both the back and the front. In part this is because both sides were often highly decorated with, for example, one side jeweled, and the other enameled. But even some of the pieces with unfinished backs are displayed this way allowing you to see their construction. This collection also includes some 19th century Renaissance revival pieces, some of which were so well-made that they fooled collectors when new.

There is also jewelry scattered throughout the museum; there were some wonderful pieces in the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine galleries surrounding the McKinlock court in the museum.

The Robie House is one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatest buildings. Located on the University of Chicago campus, it is open for tours and well worth a visit.

The Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago is conveniently located across the street from the Robie house. It is renowned for art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, Nubia, Persia, Messopatamia, Syria, Anatolia, and Megiddo, which were collected during the Oriental Institute’s excavations.

The ASJRA conference was held in the carriage house of the Glessner House Museum, an 1887 house designed by Henry Hobson Richardson. Though of the same era as the Driehaus Museum, it stands in stark contrast with the ornate Driehaus. Built in Richardsonian Romanesque style, it is fortress-like on the outside and quite simple on the inside for such a large mansion. The interiors are decorated primarily with William Morris wallpaper and textiles. It is also of interest because Mrs. Frances Glessner was a talented amateur jeweler, with two pieces in the Maker and Muse exhibit. The museum is in the Prairie Avenue historic district and there are free maps available in the Glessner house gift shops to guide you on a walk through this neighborhood.

Details

Exhibit: The Maker and Muse Exhibit will be open until January 3, 2016. A 52 page guide to the exhibit with lots of information about the jewelry comes with your admission; though this guide contains few photos, non-flash photography is allowed. The accompanying book is for sale in the museum book store and through the Amazon link above.

Where to stay: our conference hotel was the Dana Hotel, one block from the Driehaus Museum. It is also conveniently located in the River North neighborhood close to the Magnificent Mile shopping district and a moderate walk from the Art Institute and Millenium Park.

Where to Eat: The Driehaus is within walking distance of Rick Bayless’s flagship restaurants Topolobambo and Frontera Grill. I still remember the excellent duck tacos that I had at Frontera Grill on a trip to Chicago several years ago.

I also had a great meal with a friend at Little Goat, Stephanie Izard’s (winner of Top Chef) casual “diner”. Featuring diner style food, some with unusual twists and some more traditional, everything we had was excellent. Portions were generous and prices were reasonable (about $12-15 for large sandwiches).

Follow

Hi Lisa, love the Driehaus museum at night. It`s stunning 🙂

Hi Mandy,

I agree, it the Driehaus is gorgeous at night. The night I arrived for the conference there was a special lecture at the museum and they had lit the torches on the exterior. I didn’t realize that they wouldn’t be lit the rest of the time so I didn’t take a photo, but wish I had.

Thanks for writing,

Lisa

Thanks Lisa! L

Hi Lisa. Nice pix. I believe the gold and opal iris Marcus & Co pendant (shown with the LCT and Overbeck pieces) is the work of Gustav Manz, who supplied Marcus (and Tiffany) in the early 1900s-1920s. Best, Laura

Hi Laura,

Thank you for you comment. I checked the exhibit guide and the Marcus pendant is attributed to Manz in the guide. Thanks for sharing this information with my readers.

Best,

Lisa

Thank you, Lisa, for this fabulous review! I thoroughly enjoyed roaming through the rooms with you. Your descriptions are eloquent and you make it all come alive. Loved it! Maureen

Hi Maureen,

I’m glad you enjoyed my post and thanks for your comment. I hope you get a chance to visit the exhibit or add the exhibit catalogue to your book collection. Some of the most spectacular pieces were in vitrines right underneath the overhead lights and I couldn’t get decent photos of them but the book has great photos.

Lisa